20 January 2020

In a podcast of the series "Strategist & Strategist" (1), which is well worth listening to, colleagues from Flossbach von Storch (FvS) analyse the effects of share buybacks by companies on share prices. The starting point for their reflections was the assertion of many market participants that share prices can be manipulated by buybacks and that these can also be used fraudulently. We also have our thoughts on this topic! We have already presented them many times in our annual outlooks and will supplement them here once again in greater depth.

Introduction

In recent years, share buybacks by companies have played an increasingly important role. In 2019 alone, share buybacks in the USA amounted to USD 700-800 billion. In a buyback, a company acquires shares in its own company by buying them over the stock exchange. Such repurchases are financed either from the company's cash or through new loans. The shares thus acquired are recorded as an asset (without dividend entitlement) in the company's own balance sheet. If necessary, these shares can also be sold again by the company should the company need "cash" again at a later date, e.g. for investments. In most cases, however, the buyback is planned as a permanent buyback, so that many companies decide to "cancel" the shares at a later date. In such a case, the shares disappear on the asset side of the balance sheet and equity is also reduced on the liability side.

Criticism of the mainstream

Share buybacks are viewed critically. Most investors believe that this directly manipulates prices upwards, which could benefit management, for example, which usually has a financial advantage (e.g. via stock options) if prices rise. In addition, companies may have less funds available for important investments. Share buybacks are therefore often seen as an act of desperation by companies whose own business model is apparently no longer so profitable that further investment in it would be worthwhile.

Key messages of the podcast

In the podcast mentioned above, colleagues Philipp Vorndran and Thomas Lehr go into this criticism of the mainstream in detail and use two examples to show that a share buyback is merely a way of appropriating the company's profits and is therefore first of all a "neutral" operation. They describe the criticism of the mainstream as a simple error in reasoning and do not see any systematic distortion of share prices by the buybacks.

At this point we do not want to repeat the examples mentioned in detail. The colleagues have presented their examples very clearly and in detail. We will therefore only touch on them here and add our own thoughts.

Reflections on the examples from the podcast

Purchase from cash at book value

In principle, it is correct that a share buyback is initially nothing more than an "asset swap". The company exchanges cash for its own shares. These are to be accounted for at the purchase price. Such a transaction changes neither the balance sheet total nor the book value of a share. At least not as long as the shares remain on the company's balance sheet and are not cancelled.

If a company were to sell all its assets and invest everything in its own shares, as shown in the first example in the podcast, there would actually be no change in value in the share price. But this example is purely theoretical. It has nothing to do with the practice of share buybacks. And for several reasons.

Let us imagine a simple company. Initially, it consists of 100,000 euros of share capital (EK), divided into 1000 shares of 100 euros each. On the assets side, there are € 10,000 in the cash and € 90,000 in plant, machinery, etc. (operative business). This operative business generates € 5.000,-- income p.a. (taxes are not considered, but are by no means insignificant in this "game").

In other words: the company generates a return on equity of 5% (€ 5,000.-- return on € 100,000.-- share capital).

Now the company buys back its own shares. The question immediately arises: from whom and at what price? Let's keep the example simple for now and assume that every shareholder would be willing to sell at book value. For the € 10,000 from the cash register, the company can buy back 100 shares. The balance sheet is now as follows:

Assets: Cash 0, operations 90,000 (income 5,000 p.a.)

Liabilities: Equity: 90.000,-- (900 shares)

The book value of each share therefore remains unchanged at € 100, just as it is presented in the podcast.

However, as indicated in example 2 in the podcast, one key figure changes in this case: the return on equity. The operating business still generates € 5,000 p.a., which now corresponds to 5.56% of the reduced equity.

Which company is more valuable? One with 5% return on equity or one with 5.56%? Without evaluating other factors, the company must now be valued higher. But that is by no means all.

Purchase on credit at book value

In practice, however, companies are not only financed by equity. We therefore modify the example and assume that the company has an equity ratio of 30% before the share buyback and that the debt capital costs 3% p.a. in interest. At this interest rate the company could also take on further debt. The initial balance is as follows:

Assets: cash 10,000, operations 90,000 (income 5,000 p.a.)

Liabilities: EK 30.000,-- (300 shares á 100,--), FK: 70.000,-- (interest 3%)

The company currently generates a profit of 2,900 after interest (operating income 5,000 minus 2,100 interest). The return on equity is 9.67%, while the return on total capital employed is only 2.9%.

The owners of this company seem to be in a better position. The same company has almost twice the return on equity! The company uses a credit lever (leverage). Due to the partial financing of the company, the profit is lower due to interest, but the return on equity is higher. However, the return on total capital is lower. In the first example, the return on equity and the return on total capital are the same, since there is only equity. But in the second case it is clear that debt capital causes costs.

Now we are again conducting our share buyback at book value. So we buy back 100 shares of 100 euros each for 10,000 euros. The balance sheet is now as follows:

Assets: cash 10,000, operating activities 90,000 (earnings 5,000 p.a.)

Liabilities: EK 20.000,--, FK 80.000,-- (interest 3%)

How are the key figures changing? The book value of the shares still remains at € 100,-- (EK 20.000,-- divided by 200 shares). The profit after interest falls to € 2.600,--, because we have more FK to service, as well as the total return on capital. But the return on equity increases to 13%! A real yield turbo.

Imagine the headlines in the media when it is said that Company A was able to increase its return on equity by almost 50% in the past fiscal year. Does this not have any effect on the stock market?

Our thoughts on key issues / aspects

Are the colleagues at FvS right - or are the critics of the mainstream right? What is going on, how do the buybacks affect the stock market? We will examine the problem bit by bit and in the end it should be clear who is right.

Considerations on balance sheet structure

In the first example, without outside capital, the share buyback seems to be insignificant from an accounting point of view. However, as soon as FK comes into play, this is different. The balance sheet ratios change. Every banker knows that the equity ratio is a key factor in assessing the credit quality of a company. 30% equity is better than 20% is better than 10% is better than 0%.

In a rational market, a buy-back policy like the one in our example would therefore have to influence the factor "creditworthiness" as well as the factor "financing rate". This is where the first additional factor, which is not taken into account by mainstream and FvS, comes into play, namely changes in financing terms. If our company is also financed by debt capital, a buyback should weaken its credit rating. Investors and company managers alike should be given an indication by the market of the deteriorating risk situation, for example through rising interest costs.

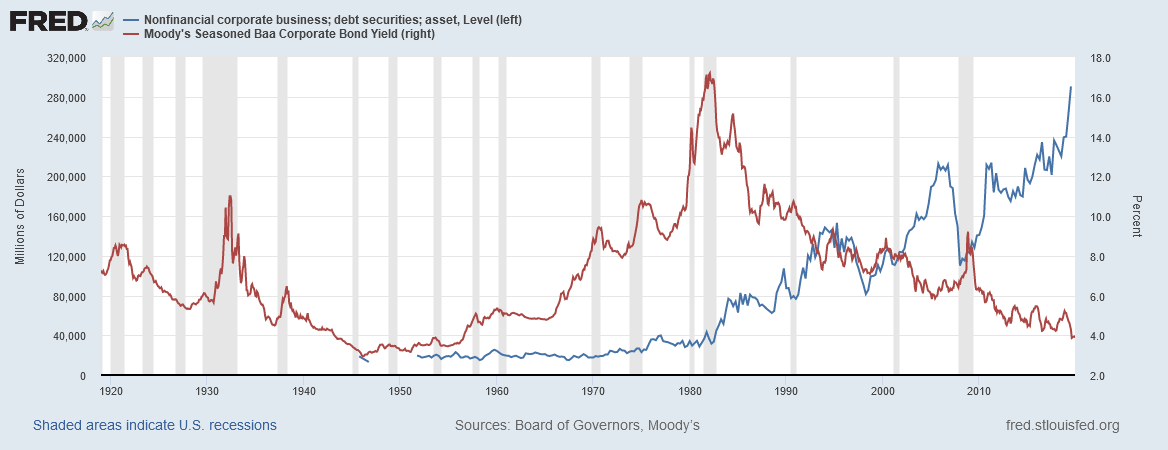

But that is hardly the case at present. This is because the interest rate market is firmly in the hands of the central banks, which have been exerting an undisputed, interest-driving influence for years. Shareholders and management board members of a company currently receive no feedback from the market that a dangerously low equity ratio has been reached, as the interest to be paid by the company seems to be unaffected by the buybacks. Investors could therefore succumb to a "credit rating illusion".

Imagine that our company does not operate a completely risk-free business. A mistake, catastrophe or the like results in a large loss from the operative business in the amount of 10.000,--. There should be. Without share buybacks, 30,000 euros of equity would be available to cover the loss, in the second case only 20,000 euros. The equity ratio after the event is only 20% in the first case and only 10% in the second. But maybe the company has committed itself in its credit agreements to always have at least 20% equity available? Then the decline to 10% would suddenly become a critical "credit event". But more on this later. The only thing that is clear is that as soon as FK is available on a balance sheet, many additional mechanisms have to be taken into account.

So it is already clear that the examples from the podcast are subject to a mistake in reasoning simply because they hide the risk dimension. By definition, a share buyback leads to a decrease in equity and thus to a reduction in risk-bearing capacity. One could also say that the volatility of the equity (= the volatility of the share) should increase. This is also logical because, as shown, creditworthiness falls and a falling credit rating should lead to a higher interest rate premium for the company. And experience shows that these spreads on corporate bonds are highly correlated with equity market volatility (= equity volatility) - as we have often shown in our annual outlooks.

In other words, a company can boost its equity returns by buying back shares. But risk-adjusted, not much should actually change. The ratio "equity return to volatility", i.e. the company's "sharpe ratio", should remain largely unchanged. (2)

And here a simple look at the empirical data shows that exactly this has not happened in recent years. Although companies in the US have bought back more shares than ever before, and although they have increased their indebtedness considerably in the process, both the interest premiums of the companies and the volatility of the shares have fallen! This should not have happened in a rational market and is a first indication that investors here are subject to a distorted perception.

Book value vs. market price

But the examples from the podcast - and thus also our modifications - are also unrealistic for another reason. In practice, no shareholder will sell his shares at book value, especially not with interest rates as they currently are. As long as the balance sheet ratios are not too stretched, the balance sheet structure should not have an excessive influence on the valuation. However, if the stock market is in a financial crisis or if investors are afraid of financing bottlenecks, companies with high levels of debt financing are likely to be more affected than those without debt.

Be that as it may: at a market interest rate of 2%, a company with a 5% equity yield is likely to be quoted slightly above book value. And a company with a 13% equity yield will certainly trade well above book value. The average price-to-book ratio is currently 3.6 for the S&P 500 and around 2.1 for the broad market (Russell 2000). So in practice companies pay much more per share than just the value of equity.

So when should a company buy back its own shares? The decisive factor is the purchase price. If the earnings per share are higher than the financing costs, a buyback may be worthwhile. But buying above the book value also creates additional risks!

As mentioned at the beginning, most buybacks are planned as "final". The shares should therefore actually disappear from the balance sheet. In our previous examples, this did not even appear on the balance sheet. But this does not correspond to reality. In practice, the shares are first taken off the balance sheet and "offset" against the equity for liability purposes. At some point, the company takes a decision to cancel the shares. If the company had acquired the shares at book value, this would have been a neutral process, which is why we were able to illustrate this in the examples above.

However, if the purchase price is higher than the book value (book value = share capital + all capital and revenue reserves or, to put it simply, total assets minus borrowed capital), then the situation is different. The purchase price would then consist of the book value plus a "goodwill". This goodwill represents all off-balance sheet assets, the "fantasy" of the business model, so to speak. It would have to be written off against current profits before it could be collected. This in turn is unintentional and so in many cases the shares are not cancelled - and thus the shares acquired are not held.

A shareholder should therefore make the following calculation to determine the actual, effective equity: Share capital + retained earnings/capital reserves minus the balance sheet value of the own shares held

As long as the shares remain in the portfolio, they do not participate in the current profits, but may still be reflected in the income statement!

This is because many US companies have been buying back their own shares for years. And practically never at book value. This has already led to curious equity ratios. The US company Kimberly Clark, for example, has virtually no equity left. This group generates revenues of USD 18.4 bn, has a balance sheet total of USD 14.5 bn (latest data from Bloomberg) and a calculated "total capital" (according to the above short formula) of USD 18 m. Of course, the company has on-balance-sheet equity and also retained earnings. But it also has considerable holdings of expensively acquired own shares.

In good times this is no problem. But what if a crisis occurs in the company. Then the company would be forced to borrow expensive equity (if it can still get it in a crisis) or to put its own shares back on the market, i.e. to sell them on the stock exchange. Would the share price then be the same as it is now when you buy back? Or would the prices probably be lower? And if the price were lower, write-downs would have to be made on own shares. The great profits would soon be over, or the dividend would possibly be at risk.

By the way: even if the company does not want to sell its own shares, it may be forced to write off its own shares. Namely if the valuation proves to be no longer sustainable. And that would be the case if the business model deteriorates sustainably. A company that finds itself on a downward trajectory could gain "momentum" through this mechanism.

Here, too, we see that the question of the impact of share buybacks cannot be answered without a detailed risk assessment. However, every investor may ask himself whether, after the experience of recent years, when governments and central banks have made every effort to keep any economic risks away from companies, investors are making an adequate risk assessment. A glance at the current high willingness of investors to bet on sustained low and even further declining volatility leaves us in considerable doubt. This, in turn, means that prices have probably been considerably distorted rather than only slightly influenced by the buybacks, as FvS suggests. This is simply because the risks are not correctly priced in.

Buying on the stock exchange

Until now, we have always assumed that the buyback mechanism was equally transparent to all shareholders and that all shareholders had the same interest in a sale. Practice is more complicated here too. In the USA, repurchases are made in certain permitted periods by private sale on the stock exchange. However, most investors do not know exactly when and how the purchases are made. For the mortals among us, not the Gold Men and JP Morgans who make the trades, the share buybacks as such only appear through the SEC mandatory disclosures after they have been made.

In daily trading practice, on the other hand, company purchases are initially just normal purchases of a share by "a major investor". And this investor has to compete in the market for the shares. Perhaps many shareholders would like to offer their shares to the company. But they happened to be on vacation or otherwise not active in the market. But the company still asks for its shares. To cut a long story short: the share buybacks can disrupt the supply/demand ratio in the short term. They have an effect on prices in the environment of the purchases - and thus there are price signals for investors. Imagine the following two cases:

Case 1: Trump tweets that sector A may suffer a disadvantage. Our company is part of this sector, but on the day of the report it happens to buy its own shares. Other companies in the industry do not do so. It is very likely that our company's share will lose less than other shares in the sector, thanks to the additional demand. What does the market think, which does not know about the buybacks? What risk perception does it have?

Case 2: The economic figures suggest a good economy. Our company, part of a cyclical industry, buys its own shares on a day when many investors want to buy because of the improved outlook. What will the share price do? Probably rise more than the market. What does the market, which is unaware of the buyback today, now think about the company?

These two cases show that the share buybacks, by their nature as buy orders in principle known to the market, but in detail hidden, can cloud investors' perception. If, as described above, adjustments in risk perception are then also missing, e.g. due to manipulated interest rates, one should not be surprised if investors misinterpret the market price signals that are distorted in this way and this ultimately leads to - admittedly non-rational - valuation distortions. The prices are not deliberately manipulated by the companies. The investors, unintentionally, very well!

The complex of share buybacks can therefore not be conclusively assessed without including behavioural economic analysis. If so, one is making a mistake in one's thinking.

Clouded view of the real economy

A further aspect in connection with the share buybacks is that it clouds the view of market participants of the actual real economic development - and thus also makes a rational risk assessment more difficult. What is meant here is the increasing divergence between the development of corporate earnings generated in the economy as a whole and the individual earnings trend "per share". As explained above, a company's earnings per share inevitably increase if the number of shares is reduced by repurchases and these purchases are refinanced at a cost below the return on assets. This gives investors the impression of a stable, straightforward earnings trend. Companies can control earnings per share and dividend policy very precisely. Especially in the USA, it is an essential task of management to increase dividends and profits as continuously as possible.

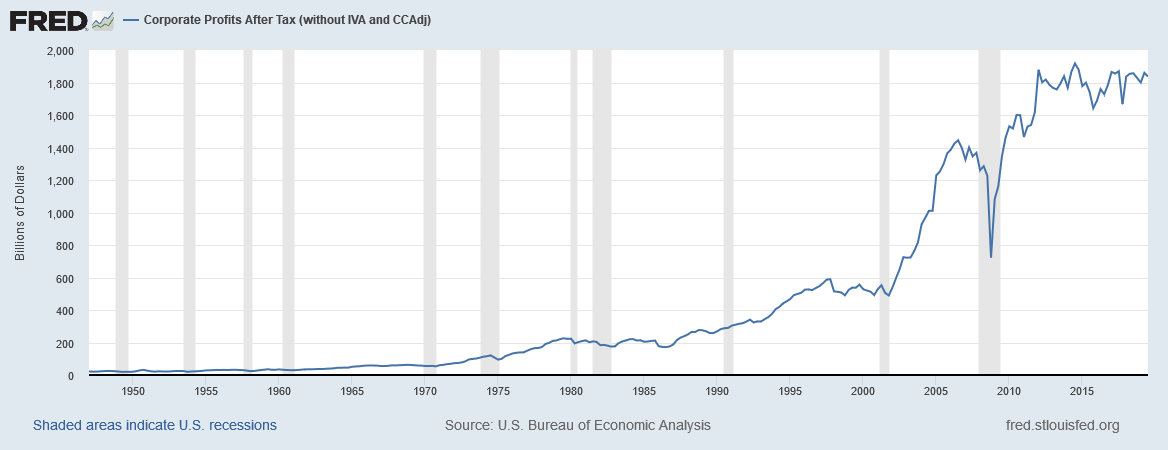

However, if this is only possible on the basis of "financial engineering", such a stable development of the company can also contribute to an incorrect risk assessment by investors. In our opinion, this is exactly what is currently happening in the USA. While earnings per share and dividends have risen steadily in recent years, economic earnings from the corporate sector have been stagnating for years. In other words, there is a negative discrepancy between the development of earnings on an economic basis and "earnings per share". However, this discrepancy is not as easily apparent to investors as the quarterly publication of profits and dividends.

For example, earnings per unit of the S&P 500 index, which is virtually the aggregated average earnings per share, have risen since 2012 from around USD 88 to currently around USD 134. This corresponds to an increase of around 52%. In the same period, the total economic profits of companies stagnated at around USD 1,879 billion. Even though this figure reflects the fact that there are a few winners and probably many losers in the US corporate sector, in the final analysis this strong discrepancy can only be explained by the targeted management of earnings per share using "financial alchemy"!

Long-term model

Finally, another effect of the share buybacks, which has been little discussed so far. In order to fully understand this point, it is necessary to have knowledge of topic 10 ("long-term equity model") from our sentix annual outlook 2019. If this information is not available to you, we will be happy to provide you with the analysis on request. Registered sentix users can download the outlook for 2019, as well as all previous issues, here The sentix annual outlook for 2020, which again contains many interesting studies, can be ordered here.

The core idea of the long-term forecast model we have presented is that the valuation of a market has a considerable influence on stock returns over the next 10 years. The more expensive a market, the lower the future returns. So far so logical. Traditionally, measures such as the Shiller P/E ratio are used for such a valuation.

However, the model we present is based on a behavioral approach and "values" stocks according to a different method. Put simply, this model measures how many shares are available to investors in relation to all available investments. The model assumes that every investor has a "standard share quota" in mind, i.e. that he or she is aiming for a certain asset structure based on his or her investment objectives etc. In practice, this would require looking at shares, bonds, money market / cash and real estate. Since the real estate portfolio is less variable, we only use the first three asset classes as a proxy.

The valuation of the stock market and thus the attractiveness or the buying / selling interest of the investors determines how many shares are available in relation to bonds and cash. If share prices rise and, for example, bond prices fall due to a rise in interest rates, the proportion of shares in all investments rises rapidly and investors are suddenly confronted with the fact that shares make up a large proportion of their asset allocation. Conversely, if equities fall sharply, the share of equities in total assets falls.

The model now implies that there is a "rebalancing" due to the individual asset allocation that investors are seeking in the long term. The interesting thing about the model is that this rebalancing is independent of the actual market valuation. The very fact that the share of equities in portfolios falls when prices fall creates demand - and vice versa.

So what does this mean for our question regarding share buybacks? Quite simply: when companies buy back shares, the share prices rise but the number of shares falls. But if companies take out credit to buy these shares, the volume of bonds increases. Although shares may have become more expensive, the share of shares in the pot of all investments falls - and triggers a rebalancing of investors (and thus further demand for shares)!

This detour does indeed explain a distorting effect on prices, which neither investors nor companies should be aware of.

In addition, there is the interest rate distortion by the central banks, which also has a positive effect on the daily value of bonds and thus also contributes to the fact that investors feel "underinvested in shares". Here it is clear that QE operations and interest rate cuts are fuelling the equity market in a banal way.

Conclusion

Now who's right? The mainstream who believes evil companies manipulate the market? Or the strategists of FvS who think everything is a non-event?

Neither one nor the other! In practice, share buybacks do indeed distort share prices upwards. But the main reason is not evil manipulation by the companies, but that investors are neither able to correctly price in the risk structure changed by the buybacks nor to correctly interpret the market price signals associated with the purchases. Added to this is the manipulation of interest rates and liquidity by the central banks, which makes an appropriate risk assessment even more difficult.

We assume that the share prices are indeed distorted upwards by the share purchases and that risks accumulate in the supposedly currently so safe shares. However, as long as the proportion of equities in the pool of available investments continues to tend to shrink from the investors' point of view and interest rates are manipulated further downwards, these risks will not become visible. The same is also true because the risks from the real economy have been successfully suppressed by politicians in recent years. However, this will not be a permanent situation.

Incidentally, share prices, especially in the USA, have already risen to such an extent that our long-term model described above only allows us to expect markets to move sideways (excluding dividends) for the next 10 years. If you are interested in an update of our model, please purchase our Annual Outlook 2020.

(1) https://www.flossbachvonstorch.de/de/der-flossbach-von-storch-finanzpodcast-kompaktes-wissen-rund-um-den-kapitalmarkt/

(2) In practice, the relationship is non-linear and also variable depending on the market environment